It’s hard to believe Netflix is 20 years old.

When Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph founded Netflix (formerly known as Kibble) in 1997, the company appeared to be little more than an upstart DVD rental business whose only real value proposition was the mail-order element of its operation. Fast forward two decades and Netflix has become one of the biggest TV and movie studios in the world, with more subscribers than all the cable TV channels in America combined. How did Netflix go from renting movies to making them in just 20 years?

By consistently doing the obvious.

For Netflix, however, doing the obvious rarely meant taking the easy way out. It meant making business decisions that were so difficult and so ambitious, few people could even see them, let alone understand them. Netflix has innovated in several key ways. They started with a frictionless DVD rental business facilitated by the internet, developed an entirely new streaming business from scratch, and finally invested in original content creation. But many of the most pivotal moves Netflix has made during the past 20 years haven’t been all that surprising. As we’ll see, it makes perfect sense that Netflix became a movie studio. It just didn’t

look that way to most people in the beginning.

Let’s look at:

- Why Netflix built its business around a single growth metric that its competitors overlooked

- How Netflix built upon its DVD rental business to launch its online streaming service

- How producing its own content became a flywheel for customer acquisition and growth for Netflix

We’re going to examine how Netflix’s growth has been propelled by developments in how, when, and where we consume entertainment, as well as the challenges that threatened to sink Netflix and where the company could go in the coming years.

1997-2006: From Video Rentals by Mail to Smart Suggestions by Algorithm

To the casual observer, Netflix might look like one of the luckiest companies in the world.

For every major change or development in the home entertainment market, Netflix always seems to be just off-screen, waiting to capitalize on the latest consumer trend. Netflix has definitely had its fair share of these kinds of opportunities, but good fortune had very little to do with the company’s early wins.

Netflix’s secret weapon wasn’t luck but rather a keen understanding of its market. Hastings and Randolph may have built their initial business around DVDs, but they knew they wouldn’t be in the DVD business forever—even if nobody else did.

“One of the biggest challenges that we had, which I think is also one of the things we did very well, is recognize very early on that if we were going to be successful, we had to come up with a premise for the company that was delivery agnostic. But if we were to come out and say, ‘This is all about downloading or streaming,’ and we said that in 1997 and ’98, that would have been equally disastrous. So we had to come up with a positioning which transcends the medium.” – Marc Randolph

Legend has it that Reed Hastings decided to start Netflix after returning a copy of Apollo 13 to his local Blockbuster. Upon returning the movie, Hastings was told that he owed $40 in late fees. Fearing what his wife would say about such a steep late fee and convinced there must a better way to rent movies, Hastings began to devise what would later become Netflix.

Although Randolph later disputed Hastings’ story about their company’s origins, Netflix did indeed set out to change the way we rented movies. In 1997, Blockbuster was the undisputed king of the home entertainment rental vertical, which made Netflix’s mail-order DVD rental business unique. As a result, when Netflix launched in ’97, many people understandably thought the business was focused exclusively on distribution—most people saw Netflix as nothing more than a more convenient way to rent movies.

Although this was a crucial element of Netflix’s early business, Hastings and Randolph never set out to be the best entertainment distribution company. They saw an opportunity to use the internet to decentralize entertainment and unbundle premium TV from the monopolistic grip of Big Cable, even if nobody else recognized their initial play for what it was. DVD rentals were never Netflix’s endgame – they were just a way for the new company to gain a tentative toehold in an intensely competitive market.

1997: Netflix launches with a video library of approximately 900 titles, with a 7-day maximum rental policy. By April 1999, Netflix’s video library expands to 3,100 titles. Rentals initially cost just 50 cents each. By January 2000, Netflix’s catalog reaches 5,200 titles.

1999: Netflix announces its new subscription model. Introduced at an initial price point of $15.95, the subscription plan allows Netflix members to rent up to four movies at a time, with no return-by dates.

2000: Netflix abandons late fees and return-by dates in favor of a monthly subscription plan priced at $19.95 per month.

2002: Netflix files its initial public offering (IPO) on May 22. Shares in the company are initially valued at $15.

2000-2003: Netflix enjoys consistent growth. However, despite increases in both revenue and subscribers, Netflix is still operating at a loss. The company reports a loss of $4.5M in Q1 of 2002 alone. Much of this loss is the result of an increase in operational expenses over costs reported in 2001.

2003-2006: Netflix continues to refine the subscriber experience by providing recommendations and suggestions for future viewing using the Cinematch ranking algorithm, which helps personalize movie suggestions. This, in turn, allows subscribers to create “queues” of titles to rent that are likely to be of interest based on their rental history and ratings given to individual titles.

“For DVDs, our goal is to help people fill their queue with titles to receive in the mail over the coming days and weeks; selection is distant in time from viewing, people select carefully because exchanging a DVD for another takes more than a day, and we get no feedback during viewing.” – Xavier Amatriain

By the end of 2006, Netflix had more than 6.3M subscribers—a 7-year annual compound growth rate of 79%—and had finally become profitable, generating more than $80M in profits in 2006. The company achieved such impressive growth by challenging incumbent players with a genuinely innovative business model and by focusing on its single North Star metric: movies watched.

Cable TV channels typically calculate their audiences based on viewership or how many viewers a TV show has. Netflix comes at this from the opposite direction by focusing on how many movies (or shows) a viewer has watched. Rather than optimizing individual shows to maximize the number of viewers, Netflix instead leverages its vast media catalog to optimize for movies watched per individual user. This subtle yet crucial distinction has allowed Netflix to remain focused on how to better engage viewers and iterate on its core “movies watched” metric through key product initiatives such as its CineMatch recommendation algorithm.

While many analysts doubted the viability of Netflix’s subscription-based model in 1999, this was key to the company’s success because it positioned Netflix as a service where you could watch as much as you want, as opposed to paying per rental. This was the real innovation behind much of Netflix’s early growth.

Even at a relatively high monthly price point, Netflix offered greater convenience and value in a (then) crowded space. It did this by eliminating two mainstays of all home entertainment business models, while simultaneously applying just enough restrictions on members to drive further growth. This allowed Netflix to not only score early wins with consumers (Keep rentals as long as you like! No late fees!), but also helped the company to further differentiate itself from the Blockbusters and the Hollywood Videos while increasing revenue.

“While there are many explanations for the growth of subscriptions, it is undeniably driven in part by a frustration with the onslaught of advertising that we are subject to. Advertising has always been a ‘tax’ on our attention.” – Bob Gilbreath

The financial challenges that Netflix experienced from 2000-2003 meant that diversifying its service offerings was as much a business necessity as a response to external forces. The company was still several years away from debuting the streaming service we know today. However, behind the scenes, the company was already investing heavily in making Netflix a more personal, individualized experience by introducing recommendations powered by the CineMatch algorithm.

By today’s standards, the CineMatch algorithm might seem quaint. At the time, though, CineMatch was surprisingly accurate. The algorithm analyzed three factors to make its recommendations—Netflix’s catalog of movies, the ratings that subscribers had given to movies they had already watched, and the combined ratings of specific titles based on the ratings of all Netflix subscribers.

CineMatch served two functions. The first was to preemptively shore up one of the most serious threats facing Netflix as a growing company—subscriber churn. When Netflix launched in 1999, only 20% of users decided not to sign up for a Netflix subscription after taking advantage of the free trial. A decade later in 2009, Netflix boasted a 90% renewal rate—but that didn’t mean Netflix could rest on its laurels. Hastings and his team knew that if people ran out of things to watch, the risk was higher they would cancel their subscription.

The second function of CineMatch was to make it easier for Netflix subscribers to find more of what they liked, faster—an aspect of the Netflix experience the company remains focused on even now. The CineMatch algorithm wasn’t just a ploy to increase customer retention. It marked the beginning of a heightened focus on the experience of using Netflix. Just as scrapping late fees had done away with one of the defining conventions of the home entertainment rental market (conventions that also happened to be deeply unpopular with consumers), Netflix wanted to eliminate another drawback of the typical movie rental experience—wasting time renting a bad movie.

Netflix knew that, for all its innovation and ambition, growth came down to one dimension: subscribers. In a letter to investors, Hastings outlined Netflix’s growth strategy for 2007, which focused on growing the company’s DVD subscriber base in anticipation of the forthcoming shift from rentals to streaming. This had been Netflix’s plan all along.

“Our strategy for achieving online movie rental leadership is to continue to aggressively grow our DVD subscription business and to transition these subscribers to Internet video delivery as part of their Netflix subscription offering.” – Reed Hastings

Netflix knew that its growth strategy was working. By making it easier for people to find and rent the movies they loved, the company had built a relatively small but growing subscriber base. Netflix knew it wanted to further expand its subscriber base through its DVD rental business before transitioning them to its online streaming service, even if nobody else saw what the company was doing. And, while its competitors remained focused on the short-term, Netflix was busy developing and investing in the technical resources the company would need to grow even further.

However, while Netflix had weathered many of the storms that threatened to sink the growing company, the perils Netflix would face in 2007 would test Hastings’ company like never before.

2007-2012: Streaming Video Hits the Mainstream, DVD Bites the Dust

“We named our company Netflix in 1998 because we believed Internet-based movie rental represented the future, first as a means of improving service and selection, and then as a means of movie delivery.” – Reed Hastings

2007 was a huge year for Netflix. Although Netflix’s DVD business was growing rapidly, the company decided to permanently transform the business by launching its first streaming product, Watch Now.

The introduction of streaming was truly radical for that time. Netflix’s pivot to streaming wasn’t all that radical—as we’ll see, it was actually a logical extension of what the company had already been doing. The fact that Netflix was willing to essentially bet the entire company on streaming, however, definitely was radical.

Consumer demand for streaming video was practically nonexistent. For one, streaming technologies in 2007 were terrible. Even the fastest broadband connections lacked the capacity to handle the bit rate of higher-resolution video, which meant overall video quality was poorer than DVD. When Netflix launched its streaming product, Watch Now was only compatible with computers running Windows and would only work in Internet Explorer after users downloaded an applet to make the video player work.

“Business is going to get a lot more competitive as Netflix goes from DVDs to streaming. There’s a lot of talk about how great online video is, but the available streaming content for Netflix is pretty weak.” – Michael Corty

Although many people thought Netflix was crazy to stream movies over the internet, this was the most logical move the company could have made given its business model. Netflix’s primary goal has always been to reduce friction to accessing entertainment. It first did this by refining and improving its DVD-by-mail service by introducing faster delivery, building more distribution centers, and eliminating fees. Before making the switch to streaming, Netflix essentially aggregated physical DVDs into warehouses, then used the internet to deliver them to subscribers. With streaming, Netflix instead aggregated entertainment content onto servers, then distributed that content instantly to customers.

By 2007, interest in DVD as a home entertainment format was beginning to wane. After two years of stagnating sales, the DVD market shrank by 4.5% in 2007, the first time that year-over-year DVD sales had fallen since the format was introduced 10 years earlier. Even though Netflix’s DVD rental business was growing and generating revenue, Hastings and his team knew it wouldn’t last. They had to future-proof the business they had built, so Netflix went all in on streaming video.

Rather than focus on improving delivery of physical DVDs, Netflix would reinvent entertainment delivery by providing its subscribers with instant access to thousands of titles that they could binge-watch on any device. While cable companies were preoccupied with traditional business models and quarterly revenue targets, Netflix was already looking a decade into the future and beyond.

There was just one tiny flaw in Hastings’ plan – the technology required to build his bold new vision of home entertainment didn’t exist. Undeterred, his company invested more than $40M in the development of new streaming technologies in 2007, the year when Netflix launched its streaming service, Watch Now.

This was the real risk for Netflix. Even though its core business was growing and performing strongly, Hastings decided to invest time, money, and capital building a streaming product when there was no consumer demand and few people thought the idea could even work. However, because hardly anybody thought it would work, even fewer companies actively pursued it. By the time everybody else caught on, Netflix had the best streaming technology, the largest library of titles, and the biggest subscriber base.

2007: Netflix introduces its online streaming service, Watch Now. The service launches with 1,000 titles and is included free in Netflix’s $5.99 per month physical DVD subscription tier.

Technically, Netflix wasn’t the first online streaming video service. (That honor goes to iTV, an impossibly ambitious project out of Hong Kong in the late ’90s.) Netflix would, however, become the first streaming success story.

2008: Netflix announces it will stop DVD retail sales just one week after debuting Watch Now on Mac platforms. The announcement comes less than one month after Netflix announces its partnership with premium American cable TV network Starz, which gave Netflix subscribers access to more than 2,500 movies and TV shows.

Retail sales had been a reliable and proven revenue stream for the growing company for years, but the decision to cease sales coinciding with the launch of a new product revealed that retail sales were never part of Netflix’s mid- to long-term growth strategies.

2011: Netflix announces the rebranding of its DVD rental business, which it calls Qwikster. Netflix planned to split its streaming business and its DVD rental business into two distinct subscription packages: Netflix for streaming, and Qwikster for rentals.

The decision was immediately and powerfully unpopular with subscribers and investors alike. The move reignited debate about the company’s future prospects, and some begin to question Hastings’ leadership. The decision was seen as a cash-grab by many subscribers, as customers would have to pay two separate subscription fees if they wanted to rent physical DVDs and access Netflix’s streaming service.

The announcement, which followed a deeply unpopular price increase that went into effect in the summer, causes approximately 800,000 subscribers to abandon the service. Analysts seized upon Netflix’s mistake as proof of the company’s imminent downfall. Less than one month after announcing Qwikster – before the service even officially launched—Hastings scrapped the plan entirely.

2011: Despite its missteps and the initial damage of the Qwikster incident, Netflix finishes 2011 on a high note. Between the launch of Watch Now in 2007 and the end of 2011, Netflix increases the number of subscribers from 6 million to 23 million, an increase of 283% in just four years.

The launch of Watch Now was a great example of Reed Hastings’ true vision for what Netflix could be. At the time of Watch Now’s launch in 2007, the company was in trouble. Analysts and investors were concerned, and audiences were underwhelmed by Netflix’s new platform. Some founders might have backtracked, but Hastings forged ahead with his plans for streaming regardless, even when it seemed like he was backing a losing horse.

Part of what made Netflix’s transition to streaming so brilliant was that few other people saw the value in pursuing streaming video. There just wasn’t enough consumer demand to justify the costs of developing new streaming technologies. With low perceived value, Netflix was able to develop and innovate with its Watch Now service with relatively little competition.

The company was also able to negotiate cheap licensing deals with networks like Starz. In 2008, Netflix and Starz entered into a four-year agreement that gave Netflix access to a library of 2,500 Starz titles in a deal reportedly worth $30M. The quality of some of these titles may have been a little lacking, but the quality of the movies themselves wasn’t important—laying the foundation for its future streaming service cheaply and with virtually no meaningful competition was what mattered.

“While mainstream consumer adoption of online movie watching will take a number of years due to content and technology hurdles, the time is right for Netflix to take the first step. Over the coming years we’ll expand our selection of films, and we’ll work to get to every Internet-connected screen, from cell phones to PCs to plasma screens.” – Reed Hastings

Ultimately, Hastings was right to bet big on streaming video. The launch of Watch Now put Netflix on the path to its eventual transformation into the entertainment colossus we all know and love today. But the introduction of streaming also revealed a critical weakness in Watch Now as a platform— very few people were happy watching movies on their PC or laptop using Internet Explorer. Although the quality of Watch Now was quite poor at launch, what mattered was that Watch Now worked. Demand for streaming was low, but it was there—all Netflix had to do was build a better streaming product with broader appeal.

Netflix’s investment in its streaming platform would also allow the company to vertically integrate itself into its own digital infrastructure when it began producing its own content years later—another great investment in Netflix’s growth and demonstration of smartly building upon earlier successes.

The Qwikster incident could have sunk lesser companies, but Hastings and Netflix handled the fallout almost perfectly. In an unusually frank blog post, Hastings assumed full responsibility for the Qwikster debacle. By listening to its customers, responding quickly, and acknowledging the role of poor executive decision-making, Netflix was not only able to get in front of the situation in the media but even managed to turn the incident into a positive PR exercise in damage control and executive accountability.

“I messed up. I owe everyone an explanation. It is clear from the feedback over the past two months that many members felt we lacked respect and humility in the way we announced the separation of DVD and streaming, and the price changes. That was certainly not our intent, and I offer my sincere apology.” – Reed Hastings

By 2012, Netflix’s relationships with several studios and media publishers had become strained. Seeking a bigger slice of the Netflix pie, Starz canceled its licensing agreement with Netflix, which resulted in thousands of movies disappearing from Netflix’s streaming service overnight. Licensing other networks’ content was becoming increasingly costly and complex for Netflix – and so the company was forced to reinvent itself yet again.

2013 – Present: Netflix Conquers the World

The period from 2007-2012 may have been the most tumultuous in Netflix’s history, but from 2013 onward, Netflix continued to defy expectations and reinvent the entertainment business. The first step? Reinventing itself as a TV and movie studio.

2013 saw Netflix dive headfirst into the world of original programming with its high-profile political drama, House of Cards. The show, which received rave reviews from critics and fans, marked a crucial turning point in Netflix’s growth as a company. Netflix had finally begun to realize its ambitions of being a one-stop-shop for original content, distributed via Netflix’s proprietary platform. Although transitioning from licensing content to producing its own movies and TV shows might seem counterintuitive for an engineering company, it made perfect sense for Netflix. The more content Netflix produced, the more subscribers it attracted. This, in turn, resulted in higher revenues, which meant more funding for original content in a virtuous cycle of constant growth.

Netflix had grown enormously prior to 2013, but the company recognized that its growth was largely limited to a single dimension: subscribers. By the end of 2013, Netflix had more than 44M subscribers, an increase of 33% from 2012, with total revenues of $4.3B, up 21% from 2012’s figures. However, all the technical innovation and original programming Netflix had invested in would ultimately mean nothing if the company couldn’t continue to attract new subscribers.

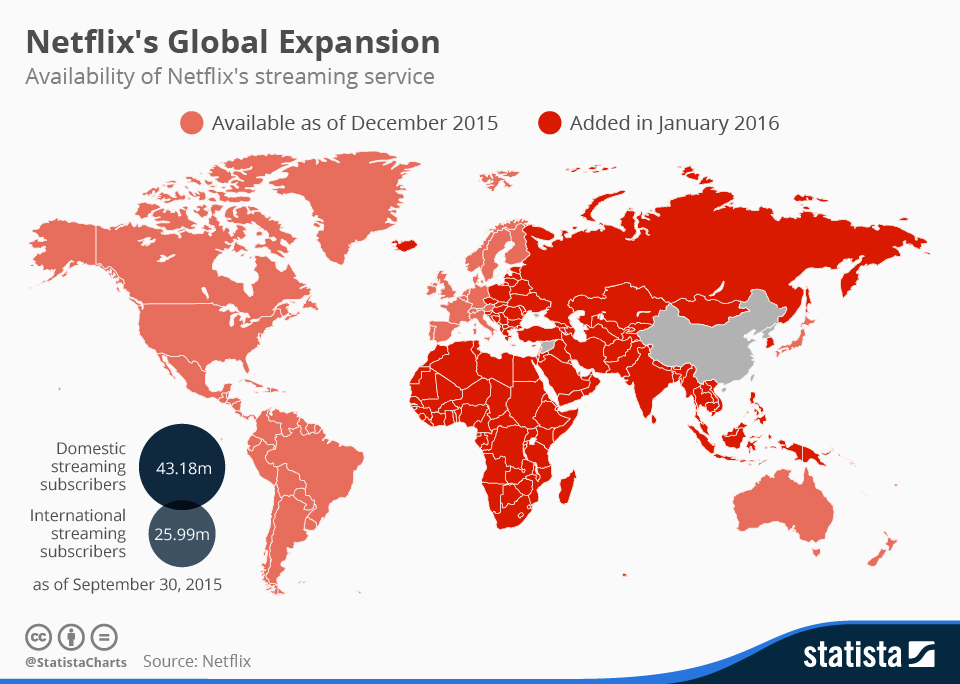

This is what drove Netflix’s incredibly ambitious, almost overnight expansion into practically every major international entertainment market in 2016. This, in turn, would feed Netflix’s ravenous appetite for original content with domestically produced foreign shows and movies for the company’s newly acquired overseas audiences.

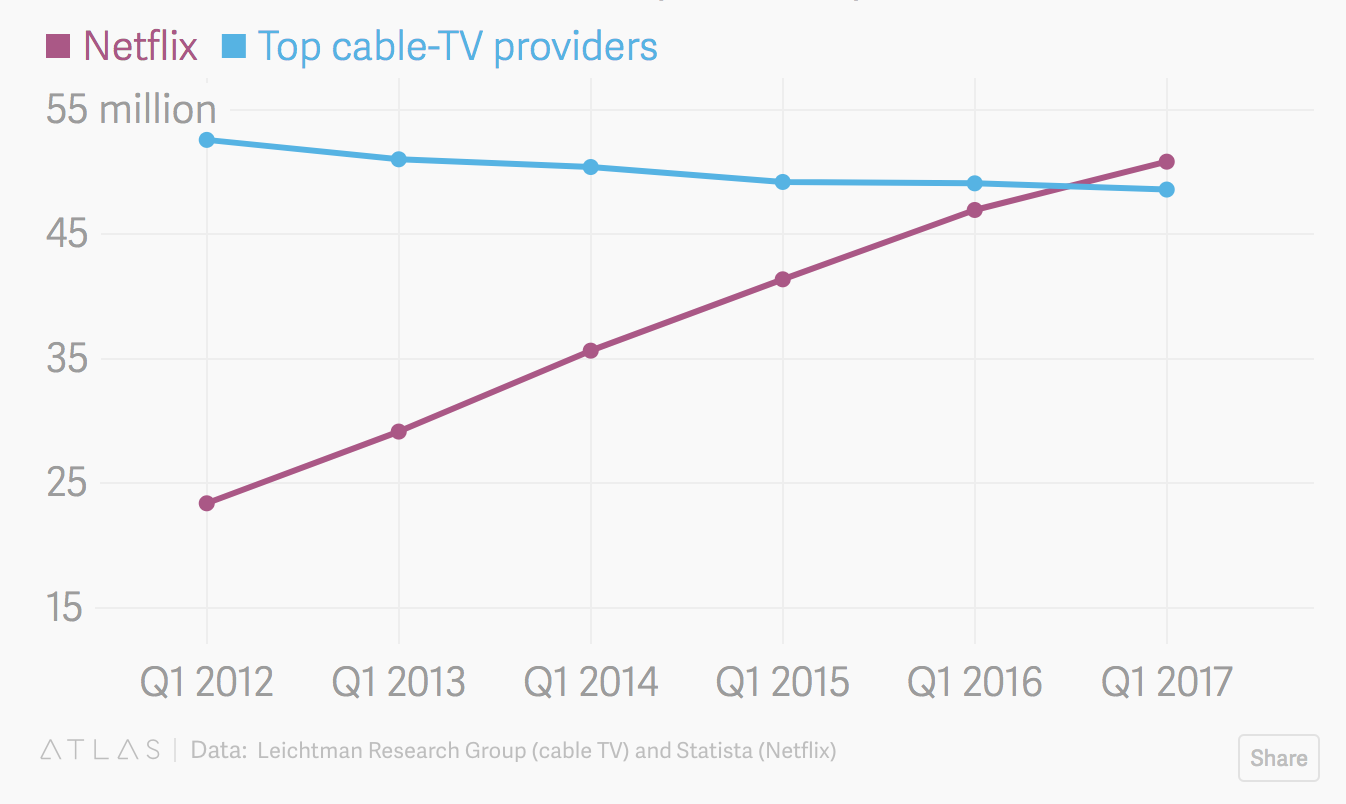

From 2016 onward, Netflix seemed practically unstoppable. The company’s programming received numerous awards and accolades, including 54 nominations at the 68th Primetime Emmy Awards. Netflix’s feature films became increasingly ambitious and attracted some of Hollywood’s most prominent screenwriters, directors, and actors. Then, in 2017, Netflix achieved what might have once seemed impossible: the number of Netflix subscribers eclipsed the total number of cable subscribers in the United States.

Netflix had effectively become the largest entertainment provider in the world—and showed no signs of slowing down.

2013: Netflix debuts the political drama, House of Cards, its first high-profile original production. Although Netflix does not release viewership data for any of its titles, Nielsen estimates that House of Cards routinely attracts audiences comparable to those of major cable network TV shows.

2013: Netflix introduces user profiles as part of a limited rollout on Apple TV. The feature is rolled out to all Netflix subscribers in August.

2015: Netflix releases its first feature film, Beasts of No Nation. The film, which had a budget of $6M and depicts the horrors of war from the perspective of a child soldier in an unnamed African country, was released on Netflix’s streaming service and in a limited theatrical release in the U.S. simultaneously—another first for Netflix. Shortly after Beasts of No Nation is released, the film is boycotted by four major American cinema chains, which claimed Netflix’s simultaneous streaming release violated the traditional 90-day window of exclusivity enjoyed by cinemas.

The release of Beasts of No Nation pit Netflix against yet another powerful enemy: mainstream movie theaters. Until the release of Beasts of No Nation, no other company had dared attempt to disrupt the traditional entertainment production pipeline so audaciously, especially regarding theatrical release timelines. The film failed spectacularly at the box office (grossing just $50,699 nationwide with a theater average of $1,635), but Netflix was pleased with the performance of the film on its streaming service.

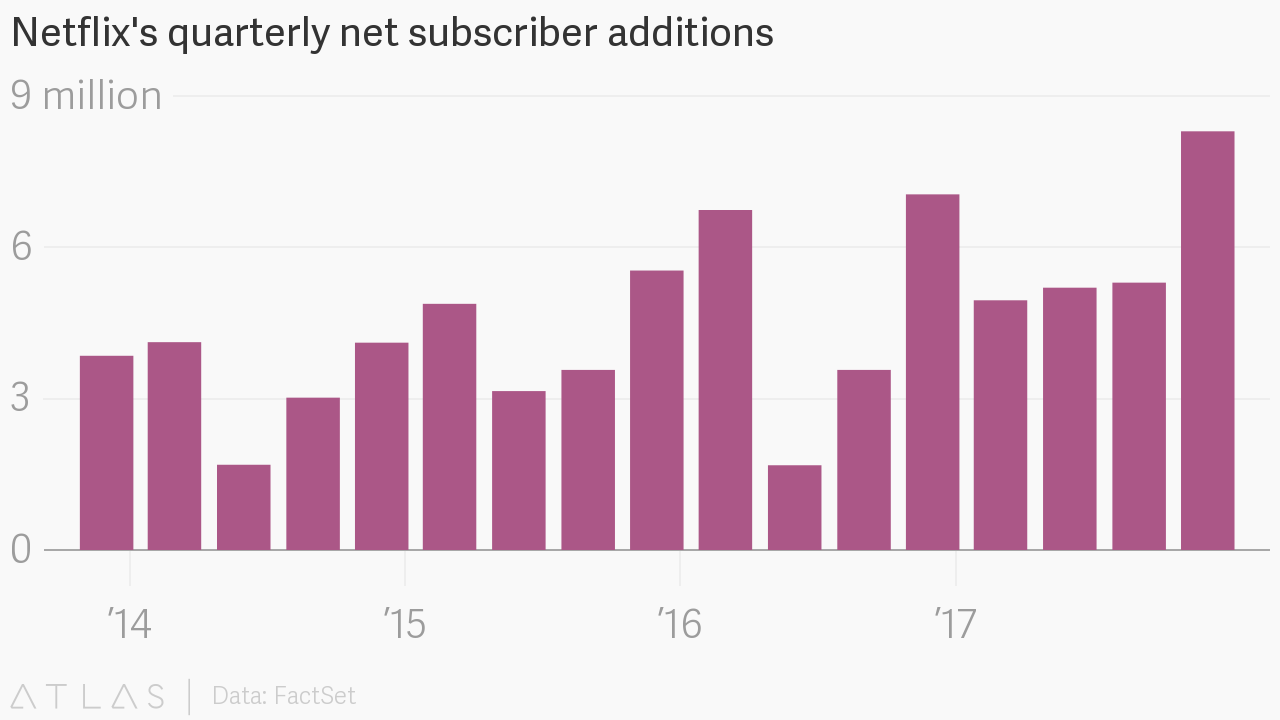

2016: Netflix goes live in 130 countries worldwide simultaneously. In a single step, Netflix transitions from an American company to a global media organization. Netflix gains more than 7M new subscribers in Q4 of 2016 as a result. Later that year, Netflix receives a record-breaking 54 nominations at the 68th Primetime Emmy Awards for its original programming. Amazon receives just 16 nominations for its own programming.

2017: The number of Netflix subscribers surpasses the total number of cable TV subscribers in the United States.

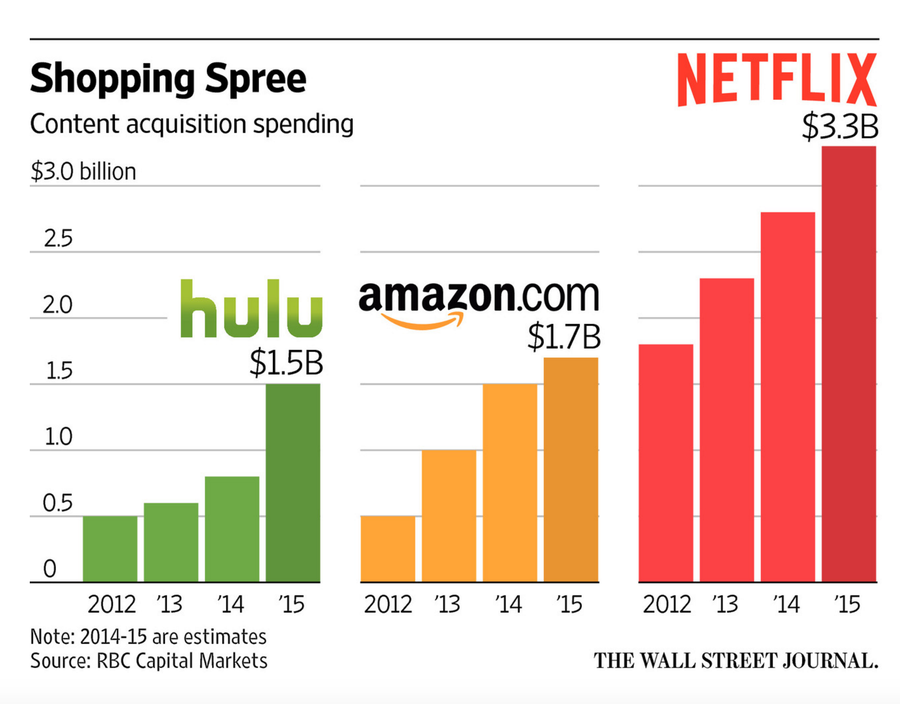

2017: Netflix plans to spend $8B on content in 2018, an increase of $2B from 2017.

2017: Netflix adds a further 8.3M new subscribers in Q4 of 2017—a new quarterly growth record for the company and a year-over-year increase of 18%. The sharp increase in subscribers coincides with the return of several fan-favorites to Netflix, including season two of the smash-hit nostalgic horror series Stranger Things, new episodes of dystopian science-fiction show Black Mirror, and a second season of Netflix’s popular historical drama, The Crown.

Although making the leap from licensing content to producing it might seem like a stretch, it made perfect sense for Netflix’s model. Original TV and feature-film productions have high upfront costs. But once that content exists on Netflix’s platform, those shows and movies become evergreen content for Netflix to attract new customers and retain existing ones around the world.

It’s difficult to overstate just how pivotal House of Cards was for Netflix. For one, the show introduced subscribers to the concept of Netflix Originals, which told viewers they could expect to see more exciting, new, and original programming on Netflix in the future. However, Netflix wasn’t producing original content for its own sake or to pad out its catalog. Netflix was laser-focused on producing not only original programming but content that was as good—if not better—than the best shows on network TV.

Another factor that distinguished House of Cards from rival cable and network shows was the series’ budget. Boasting a production budget of $100M, House of Cards‘ budget was vast for an as-yet unproven show and virtually unprecedented for a non-HBO television production. Throwing so much money at its first real foray into original programming was seen as a gamble for Netflix, but it also demonstrated the company’s commitment to producing top-notch programming from the outset.

Something else that helped House of Cards stand out was the impressive roster of creative talent behind the show. Hollywood heavyweights including director David Fincher (Fight Club, The Social Network) and actor Kevin Spacey were both attached to the series, lending the new show some much-needed celebrity star power.

The real genius of House of Cards wasn’t the show’s budget or the Hollywood names behind the project, however, but in how the show was released. By releasing every episode of the show’s first season simultaneously, Netflix introduced audiences to the concept of “binge-watching,” a development that would fundamentally change the way we watch TV. This wasn’t a marketing ploy or mere gimmick—Netflix wanted to deliver a better experience to subscribers. Who wants to wait a whole week to see how last week’s cliffhanger concludes, or suffer through 20 minutes of advertising for a 40-minute show?

Of course, Netflix wanted to change the way we watched TV everywhere, not just in the United States. If streaming video on the internet was Netflix’s most prescient business decision, the company’s overnight expansion around the world was the most ambitious. The sheer scale of Netflix’s international expansion would have given other companies pause, but Netflix had been busily readying itself for global domination for more than two years.

To find new subscribers in overseas markets, Netflix established agreements with cellular and cable network operators in each regional market. Although these agreements took months or even years to finalize, they were mutually beneficial. Netflix gained millions of new subscribers in overseas markets almost instantly with no need for international advertising campaigns or licensing agreements, and cellular providers gained a competitive advantage over domestic competitors by bundling Netflix into their plans. With more subscribers comes more revenue, which can then be invested back into original content—the same virtuous cycle of constant growth we identified earlier.

Netflix’s approach to its international expansion is another great example of how the company has continually built upon its previous successes. Netflix had been bartering with media publishers abroad for years; the company’s new allegiances with foreign cellular and cable companies was merely a new way to broker similar deals. Netflix’s overseas expansion also laid the foundation for much of the original foreign programming that has proven popular with English-speaking audiences, such as German science-fiction drama Dark, Japanese reality TV franchise Terrace House, and Swedish detective procedural Wallander.

Of all the milestones Netflix has reached, eclipsing the total number of cable subscribers in America was an amazing achievement. Not only did Netflix go from being an upstart DVD rental business to one of the largest entertainment production companies in the world in less than 20 years, it also managed to consistently innovate in verticals that many analysts and experts deemed impenetrable before Netflix muscled its way in.

Where Netflix Can Go from Here

With Netflix’s credentials as a serious player in TV and feature-film production well established, Netflix seems poised for even greater success in 2018 and beyond. Predictably, Netflix remains strongly committed to producing original programming, and the company is reportedly planning to produce around 700 Netflix Originals in 2018 alone, having increased its content budget from $6B to $8B.

Competition from rivals including Amazon and Hulu will likely intensify in the coming years, but Netflix still has plenty of options:

1. Augmented and virtual reality content

It’s practically impossible to speculate about the future of home entertainment—and, by extension, the future of Netflix – without talking about augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR).

Netflix’s CEO Reed Hastings has been vocally skeptical about AR and VR in the past. Hastings believes that VR is particularly ill-suited to TV and film because binge-watching is a lot more difficult due to the physical sensations that make VR so immersive. (If you’ve used a VR headset, you’ll know what he’s talking about.) However, with Amazon, Hulu, and other content providers betting big on AR and VR, Netflix may have little choice but to embrace these emerging technologies if it wants to retain its crown as the king of home entertainment.

“We’re experimenting with things, we’re looking at things, but we have no concrete plans. It’s a very early phase, so we’re gonna learn some things with no commitment other than to have the Netflix TV shows and movies be available within the headsets.” – Reed Hastings

2. Better shows, driven by data

Currently, Netflix uses the data it knows about us to optimize which shows we’re shown in our discovery queues. However, with so much data at its disposal, Netflix is uniquely positioned to produce substantially better programming using this same data.

With all of the data Netflix has about us and the shows we watch, Netflix isn’t just equipped to get people to watch more shows but to actually make better shows. A more data-centric approach to TV production could be one area of growth we may see as competition for audiences intensifies in the coming years.

3. High-profile acquisitions

Media consolidation is one of the single most important trends in entertainment today. With several mega-mergers fundamentally reshaping the media landscape in North America and around the world, Netflix may find itself negotiating strategic acquisitions of major media publishers to acquire existing intellectual properties, broadcast rights, and service providers. For example, Disney’s acquisition of 21st Century Fox, a deal that will see Disney assume indirect ownership of Netflix rival Hulu, may force Netflix to look beyond its own backyard so that the company can effectively preempt competing programming.

3 Key Lessons to Learn from Netflix

It’s been a wild ride for Netflix over the past two decades. What can we learn from the company’s journey?

1. Identify the one metric that can grow with your business

It’s no secret that most new businesses fail. Some companies don’t make it because they take too many risks, but just as many fail because they don’t aim high enough.

In the early days of your business, it’s crucial to identify a massive potential market that you can grow into. Google may be one of the biggest technology companies in the world, but it still cares about how many searches are conducted every month. Facebook may have 2 billion users, but it has always cared how active those users are, and how it can maximize engagement of those active users.

So how do you find your North Star metric?

One of the best ways to identify the core growth metric that will grow with your business is to examine the usage data that you already have. You want to find levers that will allow you to increase product usage and retention. Early on, your North Star metric can be as simple as increasing your total active user base. Later on, you’ll want to identify specific actions users take that correlate with long-term retention.

It’s vital that everybody in your company is on the same page regarding your growth metric. Devising technical goals around your core metric is practically impossible if data is only available to a handful of people. Once you’ve identified your core growth metric, make all data surrounding this metric (and associated goals) available to everybody, from your engineers to your customer success reps.

Once you’ve identified your core growth metric, it’s time to think about the goals associated with that metric. In the early days of its growth, Dropbox measured its success by how many users actually placed at least one file into storage. Similarly, Slack focused on getting companies to send at least 2,000 messages because that was the point at which Slack users really began to understand the benefits of the platform. How are you driving growth around your core metric?

2. Obvious moves aren’t necessarily dumb moves

Just because people expect your business to do something doesn’t mean it’s the wrong thing to do.

Not every idea has to reinvent the wheel. The best decisions are the ones that help your business grow, not the ones that only keep your competitors on their toes. Just as the simplest explanations are often the best explanations, sometimes the most obvious moves are the ones your business must make if you want to survive.

However, that’s not to say that the best moves are always obvious. In Netflix’s case, the decision to start streaming video via the internet was, in hindsight, almost painfully obvious. But at the time, Hastings’ decision cast doubt on both his leadership and the company’s future. Imagine if Hastings had listened to the naysayers who thought streaming was nothing more than a fad. Where would Netflix be today?

If your company is at a critical growth stage, think about:

- How to solve your customers’ problems and make their lives easier. Very few people use products for the sake of using them. People use products to solve their problems and make their lives better. To help your customers, ask yourself one simple question: “How am I making my customers’ lives easier with my product?”

- How to improve your product. It’s all too easy to become married to unpopular features simply because of how long they took to develop – a classic example of the sunk cost fallacy. If a product feature is unpopular with your user base or going unused by a majority of your users, pruning it is an obvious move. It’s also the right move. It’s more important to keep your customers happy than it is to keep your competitors guessing.

- How to solve the hardest problems, not the most interesting problems. The most interesting challenges facing your engineers may not necessarily be the most urgent problems facing your users. It’s crucial to remain focused on the most difficult problems your product aims to tackle rather than the problems your engineers find the most interesting. The hardest problems may not be as exciting to solve but doing so will make your customers love your product, which will drive growth.

3. Focus relentlessly on quality

Netflix has always focused on doing whatever it does really well, whether that meant getting members’ DVDs to them faster or developing new streaming technologies. This dedication to quality – whether it be the quality of the Netflix experience or the quality of its content – is what has helped Netflix cultivate not only a vast subscriber base but a loyal audience of fans.

The problem with quality is that it’ll cost you.

Although there are exceptions, it’s generally safe to assume that the higher the quality of your product or service, the higher your costs will be. However, depending on how competitive your vertical is, the question may not be whether you can afford to make a higher-quality product but whether you can afford not to.

When it comes to the quality of your product, ask yourself some tough questions:

- Did you cut corners or otherwise compromise on product quality in your race to reach product-market fit faster? If so, what would you do differently if you had more time? Moving fast is great, but breaking things all the time isn’t.

- Looking at competing products in your vertical, do any of your competitors offer a feature or function that’s as good or better than yours? In what ways is it better? What could you improve about your product to gain a competitive edge?

- Let’s say your product itself is as good as it possibly can be at this point. How’s your customer support? What about onboarding? Or your product documentation or learning resources? Remember – product quality isn’t just about how good your product is, it’s about how well you help your customers do what they want to do.

From the Small Screen to a Big Deal

Netflix’s reputation as an innovator may be a little more generous than perhaps it deserves, but Netflix has remained true to itself and to the vision of its founders. Netflix has also managed to retain the flexibility that all growing companies need to effectively respond to a rapidly changing marketplace without losing the focus it needed to sustain such ambitious growth.

Whether there’s any truth to the tale of how a $40 late fee on a copy of Apollo 13 gave rise to one of the largest entertainment companies in the world, the rise and rise of Netflix certainly makes for an entertaining story. How that story will end is anyone’s guess—but I suspect it’ll have a happy ending.

This article is cobied from here

Read also :

Comments

Post a Comment